VANISHING HARVEST: MEDITATIONS ON THE END OF PALESTINIAN AGRICULTURE

Archive of Video Interviews and Photographs of Palestinian Farmers.

(Video interviews to be posted after editing and translating)

The first phase of this project was developed with generous support from the Palestinian American Research Center.

The personal stories of Palestinian farmers living under occupation have rarely been heard, much less recorded, preserved, analyzed and publicly presented. The void in primary-source knowledge compelled me to begin developing a multi-disciplinary visual art project titled, Vanishing Harvest: Meditations on the End of Palestinian Agriculture. The project employs oral history, photography and drawing as three investigative tools that explore, reflect on and present the experiences and narratives of Palestinian farmers in the West Bank.

My interest in recording and preserving the stories of Palestinian farmers builds on the extended work I have undertaken with Palestinian refugees living in the West Bank, the Galilee, Lebanon, Jordan and in the U.S. By recording the personal experiences and stories of Palestinian farmers, it is my intention to continue to produce oral history and photographic documents, and to present poetic visual reflections that are directly informed by personal narratives of forced displacement, land confiscations, cultural genocide, as well as Palestinian narratives of resilience and resistance in the face of systematic settler-colonial erasure and oppression.

During the first the phase of the project, I recorded the stories of farmers during their spring 2019 agricultural cycle. I also returned to Palestine in October 2019, to record the annual olive harvest. Being in the field during the olive harvest, provided me with a fruitful opportunity to document an ancient and ongoing annual agricultural ritual that still necessitates members of extended families, neighbors and volunteers working together to quickly harvest the olive orchards during their peak output. The olive harvest provided a glimpse into a mostly vanished, but once thriving culture of subsistence family farming.

The onset of the COVID pandemic in early 2020 undermined my plans to return to Palestine during the summer and fall of 2020 and 2021, in order to record additional interviews and to cultivate deeper relationships with various farming communities. I had planned to focus my field work during 2020 and 2021 on villages in the northern parts of the West Bank, while revisiting a few of the farmers in communities that I already established a relationship with. I am hopeful that I will be able to resume my travel to Palestine in 2022, in order to continue my work on this project.

I actively sought out farmers cultivating small to mid-sized plots that have been owned by their families for generations. I also interviewed a few farmers that were farming larger plots, as well as farmers and activists who were preserving the land from imminent confiscation by the occupying forces, by planting on and maintaining plots that had remained fallow. Additionally, I also recorded conversations with a few shepherds; members of three small agricultural cooperatives; and a few agronomists working for organizations that offer advice and support to small and mid-scale farmers. I also interviewed scholars and activists whose work focus on the identification of once abundant and widely used native plants, and the preservation and reintroduction in the local agricultural cycles of the nearly extinct native seeds of those traditional crops.

My project seeks to have the farmers occupy an active space in the work that I am producing. My primary objective was to engage the farmers in conversations that explored their personal experiences and conditions in relationship to their abilities to effectively cultivate their land. Another very important objective was to inquire about the survival and evolution of familial, village and regional traditions, rituals and customs that are associated with the agricultural cycles. I felt, and still feel an urgency to record elements of the intangible cultural heritage that I correctly suspected was rapidly disappearing with the decrease in Palestinian agriculture.

The personal stories that I have recorded and will continue to record with Palestinian farmers, attempt to reveal their indigenous knowledge of the land, prioritize the communities' cultural values, and disclose the way the farmers think about, and exist in the world. I often asked the men and women from the communities that I engaged with to speak of the regional customs, stories, songs, rituals and ceremonies associated with various phases of the agricultural cycle. I was surprised to discover that very few of the elders I interviewed remember the old agricultural songs and stories, and that none of the farmers I met who are under fifty years of age, have even heard those songs or stories. I also asked the farmers to speak of the important networks of relationships that existed between neighboring farming villages and how those relationships were historically sustained through trade, friendships, marriage and mutual help in times of need.

During the 2019 phase of the project, I recorded interviews with more than sixty-five Palestinian farmers and agronomists from villages located in the central and southern West Bank. I also took a few thousand photographs of the farmers, their farmland, the surrounding settlements, as well as the shrinking rural Palestinian landscape, (mostly designated as Area C) that is predominantly controlled by the Israeli occupation forces. I plan to develop this multi-phased project over the course of five to six years, and will alternate between periods of fieldwork, where I record the evolving stories of farmers, with periods of studio work, allowing me to process and synthesize the information I recorded, with the purpose of distilling it into visual works of art.

I chose to record the stories of men and women from Palestinian farming communities because my research, as well as earlier conversations with farmers, suggested that their work, their income and their agricultural traditions have been plagued by extensive challenges that are threatening their survival. The interviews I started recording in 2019 confirmed that the ongoing trials they face have driven large numbers of middle-aged and younger farmers away from their families' tradition of agriculture, their farmland, and in some cases away from their villages. The political, economic and environmental conditions that are undermining the lives and livelihoods of Palestinian farmers, appear to be forcing Palestine's once sustainable and thriving agrarian culture and traditions to the brink of extinction. The undermining of Palestinian agriculture has already initiated a critical decrease in the nation's food sovereignty and has dramatically increased the transformation of subsistence family farmers into a growing force of day laborers seeking work and wages in Israel, Israeli settlements and in nearby Palestinian towns and cities.

On a much less visible level, the demise of Palestinian agriculture is a harbinger of the loss of intangible cultural knowledge and traditions that have been sustained and passed on through generations of family farmers. The decrease in gainful agricultural activities in the West Bank, also underscores increasing ruptures between neighboring villages, undermining the regional networks of affiliations that had historically provided a broad web of community support for the farmers. Most critically, the decrease in agricultural activities allows agricultural lands that remain fallow for a few years, to be easily expropriated by Israel and to be added to their now massive and ever-expanding network of settlements in the West Bank.

Almost all of the farmers I interviewed confirmed that large segments of their agricultural, foraging and grazing lands have been confiscated by the Israeli occupying forces. This was especially true of West Bank farmers whose plots were adjacent to or in relative proximity to Israeli settlements, Israeli military bases or to lands that have been declared as "natural reserves" by the occupying colonial forces. These so-called natural reserves are all on confiscated Palestinian lands and essentially serve as additional buffers that surround illegal Israeli settlements. The declaration of an area as a natural reserve blocks Palestinians from planting, foraging, grazing sheep and goats or harvesting fruit from orchards that they own. They also block Palestinians from using natural springs, wells, or diverting water for agricultural purposes from streams that run in those areas.

The majority of Palestinian agricultural villages, along with the fields and orchards that belong to those villagers, are situated in Israeli controlled Area C of the West Bank. Travelling through parts of the West Bank to meet and speak with farmers, quickly confirms and transparently reveals that Palestinian fields, villages and towns are being effectively and systematically separated from each other by a web of: massive and unpassable Israeli settlement blocks that dominate very large tracts of land; rolling and permanent military check points that greatly hinder and regularly blocks the movement of all West Bank Palestinians; countless road barriers that can be very quickly deployed by the military; as well as roads that are designed for the exclusive use of Israeli settlers and are inaccessible to Palestinians. This network of imposed obstacles makes the ability of farmers to access and cultivate their fields, orchards, grazing as well as foraging lands increasingly difficult and in many cases impossible. It doesn't take too much time on the ground to also confirm claims that are very often repeated by farmers and agronomists that the Palestinians' land and water resources are being systematically stolen from them and diverted for the exclusive use of Israeli settlements, Israeli farms and factories, military basis and Israeli declared "natural reserves".

The methods of land theft, destruction, denial of access, displacement and harassment vary from day to day and place to place, but they are all persistently and cruelly applied by the Israeli occupying forces and by Israeli settlers. The critical condition of Palestinian farmers is indicative of the plight of all Palestinians in the West Bank. Whether expropriating thousands of acres at a grab, or uprooting one ancient olive tree at a time, the clear objectives of Israel's highly militarized settler colonial enterprise are to control Palestinian lands, to remove Palestinians from their land and to erase the Palestinians' historical affiliations to the land.

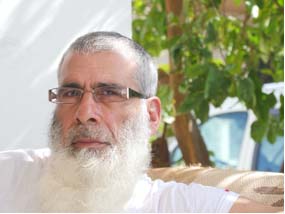

The condition of systematic expropriation of land and the coerced or violent removal of Palestinians, was very clearly illustrated during a conversation I recorded with Abu Nabil, in his village Yanoun El Foka (Upper Yanoun). By the spring of 2019, close to 90% of the village's farming and grazing land had been expropriated by the Israeli settlements that ring Yanoun El Foka, from the tops of the surrounding hills. Only five Palestinian families still resided in the village when I recorded the interview with Abu Nabil on a brilliant spring morning in early April 2019. The hilly landscape around and below the village appeared deceptively idyllic. The normally brown central West Bank hills and valleys sparkled with varying shades of green, due to the heavy rains that fell during the first three months of the year. The houses in Yanoun El Foka, are perched on the side of a steep hill and are connected by dirt roads, that would have normally been cluttered with the villagers' goats and sheep, while being herded to or from various grazing hills. Like most homes in Palestinian villages, the older ones were built of hand-cut local stone, while additions designed to accommodate expanding families, as well as new home that have been built over the past sixty years, were made of concrete. I sat with Abu Nabil in a flat section of land that connected his small concrete house with the corrugated-metal shed that sheltered his goats and sheep. Two armored Israeli military jeeps regularly patrolled the road below the village, repeatedly circling the only field that was left to Abu Nabil's family to subsist on. The jeeps occasionally stopped in positions that enabled the soldiers to observe us from a distance, without ever exiting the vehicles.

My recording of the conversation was continually interrupted by the ringing of Abu Nabil's small Nokia mobile phone. He kept rejecting the calls, but the caller kept calling back. After five or six attempts, Abu Nabil finally excused himself to answer his phone. When he returned to continue the conversation, he told me it was a neighbor from the village down the hill, Yanoun El Tahta (Lower Yanoun) informing him that Israeli settlers were uprooting a group of ancient olive trees with a bulldozer, while the Israeli military was positioned nearby to protect the armed settlers. He explained that the settlers occasionally came into the olive orchards that are still controlled by Palestinians to uproot the large olive trees in order to replant them in the settlements up the hill. He also said that the settlers would at times simply cut down or burn the ancient olive trees, leaving them to die in the fields. After receiving a couple more calls, Abu Nabil apologetically said he would have to leave and go to stand with his neighbor and try to plead with the soldiers to stop the settlers from uprooting the trees. When I asked if I could go with him, he said that the presence of an outsider could inflame the situation and provoke the settlers and soldiers to forcefully remove us.

Tragically, this was a normal day for a Palestinian farmer whose village has been almost entirely depopulated and its land expropriated by Israel's ever expanding settlement enterprise. Even the village's ancient olive trees where being stolen and relocated to the settlements in false, yet carefully staged theatrical displays that attempt to claim historical roots connecting the colonial settlers and settlements to the land. The uprooting of the old olive trees was also a blatant effort to erase the cultural and familial histories of the Palestinian villagers, whose ancestors planted the olive trees that have continuously nourished generations of farmers. What Abu Nabil and his neighbors are experiencing in Yanoun is an example of what is occurring in many agricultural villages throughout the West Bank.

Abu Nabil is a farmer who insists on persisting with his family's tradition of farming the valley and hills that surround his village. When I asked him if his son would continue to work their land, he looked away, was silent for a long moment while he stroked his graying beard and said, "Insha Allah" (if God permits.)

Unlike 1948 and 1967 when Palestinians were forcefully and abruptly removed from their land on mass, Israel's comprehensive colonial strategy has been described by a farmer as a "slow boil" of the Palestinian population. Israel's colonization strategy is deliberately pernicious, far-reaching in its everyday control and cruelty and is designed to impose broad and deep levels of suffering, misery, humiliation and despair on the Palestinian civilian population. The grinding oppression of Israel's occupation is increasingly making the life of Palestinians in the West Bank, especially those who are not willing to cooperate with or benefit from the occupation, unbearable and unsustainable. It is also creating untenable living conditions that are driving anyone with a job opportunity, to abandon their villages, and for those with the necessary means, to seek a state of self-selected exile, by departing from Palestine.

The occupation is also designed to create a high level of mistrust as well as coercive competition amongst Palestinians, for increasingly scarce resources that can be capriciously granted or denied by the occupiers. A parable about the control of populations was shared with me by the grandson of a farmer, who recalled his grandmother telling him this story when he was a child. Abu Atta's grandmother recounted a tale of two farmers whose barns were becoming infested with mice that threatened to ruin their wheat harvest. One farmer wanted to poison the mice, but the other farmer stopped him and urged a more patient approach. The farmer urging patience set small amounts of food in a series of burlap sacks that he positioned at various parts of the barn. When a sufficient number of mice would make their way inside one of the sacks, the farmer would roll up and seal the open end of the sack and slowly shake it. He explained to the other farmer "there is no need to kill them yourself. When you provide small amounts of food in an enclosed space, you will be able to trap and control them. Then when the food begins to run out and you agitate them sufficiently, they will soon kill each other."

Israel's goals of controlling a Palestine that is free of Palestinians, continues to be realized through the occupying power's coercive and carefully deployed methods of directly or indirectly controlling almost every aspect of the lives of the occupied Palestinian population. Israel's settler colonial enterprise appears to be succeeding in its goal of undermining the resources and sources of livelihood of Palestinian farmers' while creating increased levels of economic reliance on the occupying state.

Small scale farming is difficult, unpredictable and is most often not financially profitable work. Younger generations of farming families, not only in Palestine, but across much of the world are seeking alternative work that provides direct and more lucrative monetary rewards in towns and cities. This can be seen in villages throughout the West Bank. Every day, in the dark hours before dawn, thousands of Palestinian men, make their way to Israel and Israeli settlements to work as daily laborers. The stories are numerous but are not easily or often disclosed. Abu Ibrahim, A farmer from Ein Qeinia that I have known for a few years, is now increasingly unable to work his land due to his age and physical ailments. His sons have all abandoned farming and work as day laborers to support their growing families. His teenage grandson wants to drop out of school so he too can work as a laborer. Abu Ibrahim told me during a conversation that preceded the period of my fieldwork "I could feed my family for the whole year with the food I grew, but we rarely had any money. My sons earn money as laborers and can feed their families for a few days with the wages they earn, but if their work stops, or the roads are closed, which they often are, they all go hungry."

I interviewed a ninety-three-year-old farmer, also called Abu Ibrahim, who was born in and still lives in Dura El Kari'a, a small village located a few miles east of Birzeit. Dura El Kari'a has been blessed with a series of natural springs that have long assured its agricultural success. It has also been cursed by a group of Israeli settlements that overlook and partially surround the village from nearby hills. Much of the village's agricultural lands, orchards, foraging and grazing lands have been expropriated by the settlements. But the villagers still maintain some of the fields in the valley and have a long-established tradition of cooperatively and equitably sharing the critical water resource that flows from the natural springs.

When I visited the village in May of 2019, several of the fields were not cultivated and were overgrown with weeds. This was a clear sign that the neglected fields would become a target for the next stage of land confiscation by the occupying colonial powers. Abu Ibrahim spoke of working the land with his father and grandfather, as well as his brothers and cousins from a very young age. He also said that until just three years earlier, the land had adequately fed him and his family throughout his entire life and also provided some income through the sale of surplus crops in local markets. But due to his age and increasing frailty, he had to stop farming the land when he turned ninety. He said that it was only in the past few years that he and his wife had to buy food instead of eating the food that he grew. Abu Ibrahim also spoke of his ten children that still live in the village, pointing to several nearby houses. He said that none of his children were interested in farming the land that had been passed down to them through the generations. As the number of children increased, the limited plots of land that were divided amongst them became increasingly smaller. What remained of the family land had been divided amongst siblings and cousins, resulting in a series of small plots that are now owned mostly by families who have little to no interest in farming that land. Acquiring additional plots of land has become prohibitively expensive as well as completely unnecessary if Abu Ibrahim's descendants did not intend to farm the land. Abu Ibrahim also spoke of how all of his grandchildren and great grandchildren were much more interested in eating processed food that came wrapped in shinny plastic and foil packaging. He said his grandchildren also never ventured out into the fields.

I sat with Abu Ibrahim in the courtyard of the stone house that was built by one of his ancestors in Dura El Kari'a. The original one room house had additional rooms added on to it, as the family expanded, and the eldest sons started their own families while taking care of their parents and grandparents. Only Abu Ibrahim and his wife Umm Ibrahim, now lived in the simple, yet elegant stone home that once housed generations of the family. As I sat with the gracious elderly couple, I felt that I may be witnessing the last generation of Palestinians that were born into farming and had lived their whole life as hardworking and successful small-scale farmers.

The loss of land and water resources, combined with the loss of traditional markets and customers, are clear indicators of the precipitous decline of Palestinian agriculture. That decline has resulted in an increasing level of disconnection, mistrust and defensive self-interest between farmers and farmers, and especially between farmers and urban dwellers. Neighboring towns and cities have long been the primary markets for farmers to sell their goods, but many of those markets are drying up for Palestinian framers. My regular conversations with vendors at a large produce market in Ramallah as well as small neighborhood green grocers, suggests that Palestinian vendors and urban shoppers are not prioritizing their support of Palestinian agriculture by insisting on purchasing only products that have been grown and produced by Palestinian farmers. Many, if not most Palestinian consumers appear to be willing to buy cheaper produce that has been brought in from Israel and from heavily subsidized Israeli farms in the West Bank. Palestinian farmers, especially ones working smaller plots, find it impossible to compete with the lower prices of mass produced and state subsidized Israeli products.

A question that I asked many of the farmers and all of the agronomists that I spoke with, was regarding the types of assistance being provided by the Palestinian Authority to Palestinian farmers. I heard repeatedly from farmers and agronomists that the Palestinian Authority and the Ministry of Agriculture have offered the farmers very little beyond lip service. The P.A. has not helped the farmers' effort to compete fairly in the local markets, or to provide training that would help them develop new products that can reach desired markets. The P.A. has not helped the farmers secure rights to reliable water, nor aided the farmers regarding their inability to access lands that have been expropriated from them. The Ministry of Agriculture has not provided farmers with educational initiatives that would enable them to return to and maintain the use of traditional seed varieties that are cheaper to purchase and are more suitable for the local soil, the local climate and local availability of water. Nor have they assisted younger farmers in learning to use traditional methods of low water agriculture, or the use of sympathetic and cyclical planting, or ways to develop more sustainable and less toxic methods of agriculture. (All of those labor intensive but environmentally sustainable agricultural methods were uniformly practiced by recent generations of farmers, but are being increasingly abandoned in favor of modified hybrid plants that may yield larger crops but are heavily dependent on chemical fertilizers and pesticides as well as on much larger amounts of irrigation. Several farmers nervously admitted to me that the chemicals have resulted in an increase in the number of cases of cancer and leukemia in their villages and surrounding towns. But they also said that they feel trapped in an agricultural practice that requires those chemicals.) The Palestinian Authority has also done little to encourage and incentivize younger men and women to follow their parents' farming practice, or to be trained to work productively in the agricultural sector. Most importantly, the farmers recount that the Palestinian Authority has done nothing to protect them from the rapid loss of farmland. The opposite appears to be true, the Palestinian Authority's neo liberal policies appear to have allowed wealthy Palestinian developers to easily purchase land that supported orchards, farmlands as well as open space for grazing and foraging, and convert them into tracts of concrete apartment buildings, industrial complexes, unfinished roads and expansive villas. This phenomenon can be seen in the seemingly unregulated and uncontrolled sprawl that defines the expanding edges of most Palestinian cities and towns.

My pessimistic observations of the rapid state of decline of Palestinian agriculture are tempered by a few very positive signs of renewal and reengagement in the culture of farming. I will outline a few of those encounters below and plan to continue exploring various grassroot efforts to revitalize Palestinian agriculture.

One of the unexpected and heartening findings during my field work in Palestine, was the discovery of budding youth movements engaging in cooperative farming communities. The groups viewed their effort as a form of cultural survival and political resistance, that are designed to insure food sovereignty. I plan to focus more on the motivations of the cooperative agricultural movements in Palestine during the next phase of the project. The nascent agricultural cooperatives that I encountered, have been founded and are completely run by young men and women with little previous agricultural experience. Almost all of the members of the cooperatives are college educated and are relatively young. Many of the ones I interviewed live in urban settings and commute by private car or shared transportation to their farm plots.

I interviewed members of four cooperatives that have been established in lands belonging to the villages of Ras Karkar, Safaa, Fark'a and Bil'in, in the central West Bank. I also heard of a few others that I will investigate in future visits. Each of the four cooperatives operates on relatively small plots of rented or borrowed land in Area C of the Central West Bank. They have been forbidden by the occupying forces from digging new water wells or revitalizing existing ones and have been denied permits for building any permanent structures on the land they farm. They also at times find it challenging if not impossible to get to their farms due to unpredictable road closures by the occupying military forces. But the volunteer farmers, ranging in age from late teens to mid-thirties, have been very clear at outlining their objectives and extremely creative in fulfilling those objectives. A few of the objectives of the farming cooperatives are:

A. To reclaim agricultural lands in Area C that are under threat of being expropriated.

B. To engage and train young generations of Palestinian men and women in the practice of sustainable agriculture.

C. To utilize, as much as possible, native seeds and traditional low impact farming practices.

D. To provide locally grown and pesticide free produce to the local communities.

E. To invite field trips by school age kids and educate them about healthy diets and local sources of food production.

F. To raise awareness about the hazards of environmental degradation and promote a caring practice for the local as well as the global environment.

G. To develop a sustainable and self-supporting agricultural practice that would eventually provide economic viability for the cooperative's working members.

H. To encourage a discourse on the agricultural practices needed to achieve food sovereignty.

I was impressed by and developed a great deal of respect for the creative and compassionate spirits of these young farmers and look forward to documenting the evolution of their agricultural practices. The small scale, ecologically sustainable agriculture that the cooperatives are implementing, provides clear and potentially viable connections between the past and the future of Palestinian agriculture.

Another positive impact on Palestinian agriculture is being provided by professionally run organizations like UWAC (The Union of Agricultural Workers Committee), and PARC (The Palestinian Agricultural Relief Committee). Both organizations rely heavily, if not completely, on international funding, but are run entirely by Palestinian agronomists, veterinarians, hydrologists, and administrators. Both organizations provide through their regional offices, a range of educational and practical resources to farmers across the West Bank. At the core of each of the two organization's missions, is the development of policies and the promotion of practices that support food sovereignty. One of PARC's most impressive initiative has been to develop a seed bank from native plants that had traditionally been cultivated by Palestinian farmers. PARC's small seed farms and laboratory are gradually expanding an effort to grow traditionally successful Palestinian agricultural crops, collect, dry, and preserve the seeds extracted from the plants, then distribute those seeds, free of charge, to farmers who are interested in and wiling to grow those traditional crops. The objective is to break the farmers' increasing reliance on hybrid seeds that have been produced by international corporations. Those non-native seeds require intensive irrigation, and need to be frequently supplemented with chemical fertilizers as well as repeatedly treated with pesticides. The process of growing traditional crops is more labor intensive and the yield of the plants is less plentiful than the hybrid varieties, but they are infinitely more sustainable and regenerative from an environmental perspective and potentially profitable from the perspective of small farms producing healthy, pesticide free, and locally grown crops for small local markets.

In addition to providing agronomists and a veterinarian for me to interview, both UWAC and PARC were very helpful by introducing me to a few small to mid-scale farmers and shepherds whose work they encourage and support.

Another small organization that provides hope for small farmers is called Adel (Justice.) The small group operates out of a van that collects vegetables, fruit and other farm produced goods such as dried legumes, grains, honey, jams, dairy and other products made by a network of small farmers. Adel then sells the products from the van in Ramallah and Bethlehem. The van tends to target neighborhoods with relatively affluent consumers who can afford to pay the slightly higher costs of the products. In response to Adel's still limited marketing efforts, the targeted urban consumers have shown great interest in purchasing locally grown products and supporting indigenous small-scale farmers. Adel's effort provides proof that creative solutions are needed to bypass mounting restrictions. If Adel can survive and expand, it would offer an alternative model for bringing sustainably grown produce to new markets. This could lead to the survival of a larger network of small-scale farmers, while increasing the active commitment of Palestinian consumers to the survival and success of Palestinian farmers.

I observed a few other bright spots that provide tentative hope for the survival of Palestinian agriculture, some of them focus on community education, others on the preservation and propagation of nearly extinct native seeds. I also encountered several relatively young farmers who adamantly, and in some cases successfully, persist in their agricultural practices in the face of mounting challenges. Some of these small farms and creative enterprises are run by one person while others have an established organizational structure that includes small groups of volunteers. Their effort begins to offer much needed relief to beleaguered Palestinian farmers and provides a glimmer of hope that could begin to counterbalance the gloomy condition of Palestinian agriculture. Time will tell how sustainable, successful and influential the efforts of these organization will be. I am looking forward to continuing my engagement with them when I am able to return to Palestine and resume work on this project.

John Halaka

July 2021